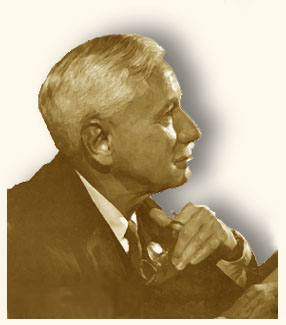

by

Will Durant

Human conduct and belief are

now undergoing transformations profounder and more

disturbing than any since the appearance of wealth

and philosophy put an end to the traditional religion

of the Greeks.

Human conduct and belief are

now undergoing transformations profounder and more

disturbing than any since the appearance of wealth

and philosophy put an end to the traditional religion

of the Greeks.

It is the age of

Socrates again: our moral life is threatened, and our

intellectual life is quickened and enlarged by the

disintegration of ancient customs and beliefs.

Everything is new and experimental in our ideas and

our actions; nothing is established or certain any

more. The rate, complexity, and variety of change in

our time are without precedent, even in Periclean

days; all forms about us are altered, from the tools

that complicate our toil, and the wheels that whirl

us restlessly about the earth, to the innovations in

our sexual relationships and the hard disillusionment

of our souls.

The passage from

agriculture to industry, from the village to the

town, and from the town to the city has elevated

science, debased art, liberated thought, ended

monarchy and aristocracy, generated democracy and

socialism, emancipated woman, disrupted marriage,

broken down the old moral code, destroyed asceticism

with luxuries, replaced Puritanism with Epicureanism,

exalted excitement above content, made war less

frequent and more terrible, taken from us many of our

most cherished religious beliefs and given us a

mechanical and fatalistic philosophy of life. All

things flow, and we seek some mooring and

stability in the flux.

In every developing

civilization, a period comes when old instincts and

habits prove inadequate to altered stimuli, and

ancient institutions and moralities crack like

hampering shells under the obstinate growth of life.

In one sphere after another, now that we have left

the farm and the home for the factory, the office and

the world, spontaneous and "natural" modes

of order and response break down, and intellect

chaotically experiments to replace with conscious

guidance the ancestral readiness and simplicity of

impulse and wonted ways. Everything must be thought

out, from the artificial "formula" with

which we feed our children, and the

"calories" and "vitamins" of our

muddled dietitians, to the bewildered efforts of a

revolutionary government to direct and coordinate all

the haphazard processes of trade. We are like a man

who cannot walk without thinking of his legs, or like

a player who must analyze every move and stroke as he

plays. The happy unity of instinct is gone from us,

and we flounder in a sea of doubt; amidst

unprecedented knowledge and power we are uncertain of

our purposes, values and goals.

From this confusion

the one escape worthy of a mature mind is to rise out

of the moment and the part and contemplate the whole.

What we have lost above all is total perspective.

Life seems too intricate and mobile for us to grasp

its unity and significance; we cease to be citizens

and become only individuals; we have no purposes that

look beyond our death; we are fragments of men, and

nothing more. No one (except Spengler) dares today to

survey life in its entirety; analysis leaps and

synthesis lags; we fear the experts in every field

and keep ourselves, for safety's sake, lashed to our

narrow specialties. Everyone knows his part, but is

ignorant of its meaning in the play. Life itself

grows meaningless and becomes empty just when it

seemed most full.

Let us put aside our

fear of inevitable error, and survey all those

problems of our state, trying to see each part and

puzzle in the light of the whole. We shall define

philosophy as "total perspective," as mind

overspreading life and forging chaos into unity.

Perhaps philosophy

will give us, if we are faithful to it, a healing

unity of soul. We are so slovenly and

self-contradictory in our thinking; it may be that we

shall clarify ourselves and pull our selves together

into consistency and be ashamed to harbor

contradictory desires or beliefs. And through this

unity of mind may come that unity of purpose and

character which makes a personality and lends some

order and dignity to our existence. Philosophy is

harmonized knowledge making a harmonious life; it is

the self-discipline which lifts us to security and

freedom. Knowledge is power, but only wisdom is

liberty.

Our culture is

superficial today, and our knowledge dangerous,

because we are rich in mechanisms and poor in

purposes. The balance of mind which once came of a

warm religious faith is gone; science has taken from

us the supernatural bases of our morality and all the

world seems consumed in a disorderly individualism

that reflects the chaotic fragmentation of our

character.

We move about the

earth with unprecedented speed, but we do not know,

and have not thought, where we are going, or whether

we shall find any happiness there for our harassed

souls. We are being destroyed by our knowledge, which

has made us drunk with our power. And we shall not be

saved without wisdom.

.