THE

AGE OF THE DURANTS

by

Robert W. Merry

THE NATIONAL OBSERVER

August 2, 1975

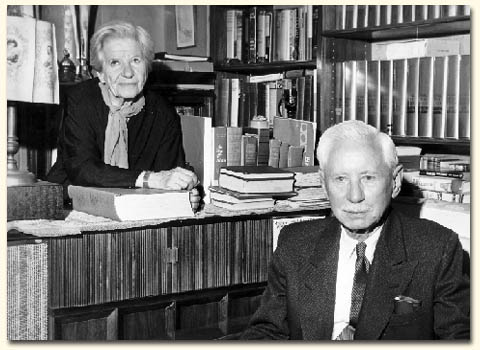

WHEN A MAN reaches 90 and he is

author or coauthor of 17 books on the history and

philosophy of the world, then perhaps he is entitled

to sit back, clasp his hands behind his head, and

bask in his well-earned eminence without having a lot

of young upstarts contradicting his historical

interpretations.

But no such privileged

existence is likely for Will Durant in his 10th

decade. His partner in toil (as well as in marriage)

for the past 62 years just won't hear of it. Ariel

Durant believes the way to maintain a measure of

youthfulness in an old man's thinking is to keep his

views under challenge. And she's qualified for the

task: Besides being a historian in her own right (and

coauthor of seven of the Durant books), she's also a

youthful 77.

Her self-assigned mission seems

perfectly acceptable to her husband, whose blue eyes

twinkle when he and his wife are engaged in friendly

debate over the significance of Western music, the

consequences of the Peloponnesian War - or how age

influences a man's view of the world.

Durant's eyes are twinkling

aplenty as he sits with his wife in a 17th-floor

suite in the St. Regis Hotel here and chats about the

essence of Western civilization, its future (or lack

of it), the role of historians, and the Durants' own

work. That work will culminate in November with

publication of The Age at Napoleon (Simon and

Schuster), the 11th and final volume in the Durants'

famous The Story at Civilization series.

Durant, a small man with

chalk-white hair and matching mustache, is taking

strong exception to that irreverent wit, Voltaire,

who said history was nothing more than a record of

man's crimes and follies. "I think that's

nonsense," says Durant. "History is the

work of inventors, poets, artists, and statesmen. It

is the product of human beings who are also capable

of crimes and follies, yes, but it is not merely the

record of crimes and follies. That's why in our books

we've been concerned with events that proved vital to

civilization. Take the Peloponnesian War, for

example; Athens took second place after that, and…”

That’s as far as he gets

before his wife cuts in with a little devil’s

advocacy.

“Was that tragic or

beneficial?” she asks.

He: "Well, Sparta wasn't

dedicated to culture."

She: "Yes, but it had

greater strength. It was more brutal, maybe, but it

reinvigorated a soft people."

He: "Invigoration?

Athenian culture declined after that."

She (flashing a smile of

anticipated victory): "Ah yes, but tell me this:

wouldn't Athens have fallen down with or without that

defeat?"

He (sinking back against the

sofa and speaking almost in a sigh): "Probably.

As usual, the death of the old religion took the

moral basis out of civilization."

Durant's resigned answer has

significance beyond the Fifth Century B.C. because

many believe the death of the old religion has, as

usual, taken the moral basis out of our own

civilization as well. "The Twentieth Century

approaches its end without having yet found a natural

substitute for religion in persuading the human

animal to morality," the Durants write in their

forthcoming book.

And many wonder whether the

West can survive the secular fervor that burst into

political significance in the French Revolution, then

spread through Western culture during the next two

centuries. "I would have to agree with Spengler

that the West is in decline," says Durant.

"The future belongs to the East."

Mrs. Durant is a little more

sanguine about Western prospects. She doesn't believe

that the West's religious decline necessarily means

its civilization is dying. Material progress has its

own sustaining abilities, she says.

But her husband, surveying

world history, can think of no moral code that

survived the death of its gods and no society that

survived the death of its moral code. “The great

experiment we’re engaged in is whether a moral

code can survive without the support of supernatural

beliefs,” says Durant. “That’s the

crux of the matter.”

Those hardly are the words you

would have heard from an earlier Will Durant, the

young man who bolted from a Roman Catholic seminary

in New Jersey back in 1911, gravitated to New York,

and fell in with some of the country's most radical

young thinkers. In those days of romantic faith in

man's inherent goodness, Durant wasn't nearly so

enamored of order or fearful of chaos. But the world

changes with the decades, and so do a man's

perceptions.

"What we're up

against," says Durant, "is the simple fact

that man is still an animal. That's the deepest thing

in his nature - the survival instinct and the hunting

instinct. Those were necessary once upon a time, when

self-preservation was the rule rather than the

pressures of society. So morality has an uphill

battle against these two inheritances. You have to

recognize the enormous difficulty in making an animal

and hunter into a citizen, a civilized man.”

“Baby,” says Mrs.

Durant, looking admiringly at her husband, “that’s

a mouthful.”

Durant smiles, then continues:

“The important thing is to

achieve liberty with order. England came close to

achieving this in its finest age, but today we live

in an age of chaos. In morality, art, music, we're

floundering around. I used to say art was the

transformation of chaos into order. Now it seems to

be the transformation of order into chaos." He

chuckles quietly. "I have it in for chaos. I

don't like chaos."

He dislikes chaos so much, in

fact, that he would rather listen to Bach, whose

baroque masterpieces reflect the order of his day,

than to Beethoven, who abandoned the aristocratic

tradition with his Third Symphony, the Eroica, and

rushed headlong toward the romantic abyss.

"Beethoven represents license, praise for

personal feeling, and free expression. That verges on

chaos."

At this point Ariel Durant cuts

in again. "You have to remember," she

admonishes, casting a quick glance at her husband,

"you have to remember that these are the

opinions of an aged man. As Will approaches the

century mark, he becomes more and more conservative

and, well, more scared. He starts feeling there's too

much innovation. Therefore, his opinions aren't

necessarily the opinions you might have heard if you

had talked to him in his gut-fighting days 30 or 40

years ago."

The former gut fighter smiles.

"I admit the indictment," he says quietly.

"I admit they are the opinions of an old

man." He raises his voice just a bit. "But

that doesn't necessarily prove them wrong."

She: "Old people have seen

so much, experienced so much, that they usually

modify the daring and adventure necessary to

youth."

He: "But that may be an

advantage. At least the old person has experienced

both forms, old age as well as youth. The young have

only experienced the one."

She: "But there are timid

elements in old age. There's something to be said for

youth and its daring."

He (taking her hand, eyes

twinkling): "Ariel speaks pretty youthfully for

a young lady of 77, doesn't she?"

A little more seriously, he

continues: "Well, old age stands for order, the

brake on the car; youth stands for liberty, the gas

pedal. Both are necessary, I suppose, but I think the

brake is more necessary." Warming to the

metaphor, he adds: "On the other hand, I suppose

the old ones sometimes keep the brake on even when

they're going uphill."

The Durants themselves never

kept the brakes on during their long uphill journey

together toward accomplishment and fame. They have

worked from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. for most of their adult

lives, including most Saturdays and Sundays. “How

else would we get it done?” asks Mrs. Durant,

adding: “But we do what’s necessary to take

time out. We go to movies once a month.” She

also notes that their Hollywood Hills, California

home is “only five minutes away from Hollywood

and Vine, so we’re not too far from mischief.”

But those 14-hour days haven't

left much time for mischief. And besides, it took

more than long hours to create the Durant legacy.

"The beauty of our lives," says Mrs.

Durant, "is that Will has a clear, rational,

systematic mind. He knows how to bring order out of

chaos." But the toil was parceled out equally.

"We developed our own system," says Mrs.

Durant. In interpreting history, the system

"includes a majority of two."

The system apparently works, as

anyone knows who has picked up one of their hefty

volumes. The Durants' works, while not profound in

historical interpretation or original scholarship,

are considered masterpieces of historical narrative.

And they are graced with a robust prose style,

elegant wit, and an abiding appreciation for history

as it actually was, including the contributions of

all the greats, near-greats, ordinary folk, knaves,

and fools who kept history on its inexorable course

toward today.

That appreciation goes back

many years, to when Will Durant was an obscure

administrator of an adult-education school in New

York City. Durant's passion for history was evident

one day as he lectured on Plato at his school. When a

New York booklet publisher happened to hear the

lecture, a career was born. "He wrote me,"

recalls Durant, "and asked me to type out the

lecture for one of his little books. I was too busy.

I refused. He insisted, and sent me an advance check

for $150."

That began a series of

publications that later formed the basis of Durant's The

Story of Philosophy, which appeared in 1925. The

book was so successful that it elevated the Durants

to what one might call - jokingly - the leisure class

and awarded them the financial independence to begin

their life's work, The Story of Civilization

series.

The series, which began in

1935, contains three volumes on the history of the

Orient, Greece, and Rome, with the rest devoted

almost exclusively to the history of European

civilization. The forthcoming The Age of Napoleon

covers the era from 1789 to 1815 and focuses largely

on the French Revolution and the rise of Napoleon.

The book will crown the Durants' long career as

historians.

"We have loved

history," says Mrs. Durant, "and our love

has been highly rewarded." Her husband is quick

to point out that their love for history never could

have been requited as it was without the success of

his first book. "That was a stroke of fortune we

had no right to expect," he says. "So we

have every reason to be grateful."

Speaking as one in a little

book called The Lessons of History, the

Durants expressed their feeling for history in

another way. “If a man is fortunate he will,

before he dies, gather up as much as he can of his

civilized heritage and transmit it to his children,”

they wrote in 1968. “And to his final breath he

will be grateful for this inexhaustible legacy,

knowing that it is our nourishing mother and our

lasting life.”

Our

thanks to Paul Natho for his historical efforts in

preserving this article.