.

|

Anybody can make

history. Only a great man can write it.

- Oscar Wilde

Fifty years of writing a book may

seem like a long period of authorship, but there is a lengthy

work that took a full five decades to write. The book is The

Story of Civilization, and the man was Will Durant.

He was once called William James

Durant. His pious French-Canadian mother had chosen the name

in deference to one of Christ’s apostles, however, rather

than out of respect (or even knowledge) of the famed American

psychologist-philosopher. In time, the youth became a compromise

of sorts; becoming an apostle for philosophy.

First, however, Durant was destined

for holy orders. Born in North Adams, Massachusetts, in 1885,

he studied in Catholic parochial schools there and in Kearny,

New Jersey. His teachers were nuns, and he practiced his religion

so fervently that no one doubted that he would become a priest.

In 1900 he entered St. Peter's Academy and College in Jersey

City, where his teachers were Jesuits, and, one of these, Father

McLaughlin, urged him to enter the Jesuit Order following his

graduation in 1907.

But in 1903 he discovered the works

of some alluring infidels in the Jersey City Public Library

-- Darwin, Huxley, Spencer and Haeckel. Biology, with its Nature "red

in tooth and claw," did some harm to his faith, and suddenly,

in his 18th year, it dawned upon him that he could

not honestly dedicate himself to the priesthood – but

how could he break the news to his mother, who had pinned her

hopes, both for this world and the next, on offering her son

in service to God?

The outcome was extraordinary, for,

while Durant was losing one faith, he was taking on another

in compensation. In 1905 he exchanged his devotion for Socialism.

An earthly paradise, he felt, would compensate for the heaven

lost in the glare of biology. Another youth attending the same

college was suffering a similar and simultaneous infection,

for he, too, had been headed for the clergy. To both boys occurred

the fascinating idea of pleasing proud parents by entering

the priesthood – but, once in, they would work to convert

the American Catholic Church to socialism. For a time, some

inkling of the size of the enterprise deterred the conspirators,

but they failed to heed the warning.

Graduating in 1907, Durant persuaded Arthur

Brisbane to offer him employment as a cub reporter -- at the

princely sum of ten dollars a week -- on the New York Evening

Journal. This was a heady change from the young man's youthful

piety, for the evening papers of New York in that summer were

featuring rape cases. The young man, dizzy with Socialism but

still mindful of his morals, found himself pursuing sex criminals,

day after day. The occupation turned his stomach, and a kindly

editor advised him to keep an eye out for some less strenuous

occupation. In the fall of 1907, he subsided into teaching

Latin, French, English and geometry in Seton Hall College,

South Orange, New Jersey. And at last, in 1909, he and his

secret associate entered the seminary that was attached to

the college and set about their earlier devised task of impregnating

Thomas Aquinas with Karl Marx. Graduating in 1907, Durant persuaded Arthur

Brisbane to offer him employment as a cub reporter -- at the

princely sum of ten dollars a week -- on the New York Evening

Journal. This was a heady change from the young man's youthful

piety, for the evening papers of New York in that summer were

featuring rape cases. The young man, dizzy with Socialism but

still mindful of his morals, found himself pursuing sex criminals,

day after day. The occupation turned his stomach, and a kindly

editor advised him to keep an eye out for some less strenuous

occupation. In the fall of 1907, he subsided into teaching

Latin, French, English and geometry in Seton Hall College,

South Orange, New Jersey. And at last, in 1909, he and his

secret associate entered the seminary that was attached to

the college and set about their earlier devised task of impregnating

Thomas Aquinas with Karl Marx.

The College had an excellent library,

and Durant was made librarian. It was there, as he moved affectionately

among the books, that he learned of the man who, beyond any

other thinker, would shape his life. Spinoza's Ethics Geometrically

Demonstrated was a revelation to him in its heretical content

and its mathematical method -- but, above all, in the personality

it revealed of a philosopher actually living his philosophy,

merging practice and precept, and dedicating himself, in poverty,

simplicity and sincerity, to an attempt to understand the world.

Almost memorizing that book, Durant then came to see very clearly

the absurdity of his conspiracy, and he shuddered at the lifelong

insincerity it would have imposed upon him. In 1911 he left

the Seminary, his only possessions four books and $40, and

migrated to New York. A separation between Durant and his parents

ensued, and it was years before his mother and father would

forgive him.

From a peaceful and orderly seminary existence, Durant

passed on to the most radical circles in the "bedlam" of

Manhattan. He tried -- and failed -- to convert Emma Goldman

and Alexander Berkman from anarchism to socialism. In 1911,

he became the teacher and (as he put it) chief pupil of the

Ferrer Modern School, an experiment in libertarian education.

A sponsor of the school, Alden Freeman, took a fancy to the

shy instructor and treated him to a summer tour of Europe to "broaden

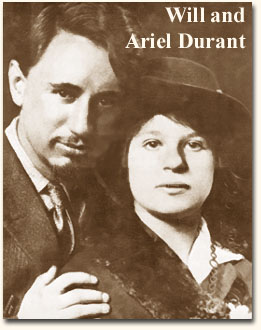

his borders." Returning to the States, Durant fell in

love with one of his pupils, whose sprightly vivacity led him

to call her "Puck" and, in his writings, "Ariel" --

the names by which she became known to the rest of the world. From a peaceful and orderly seminary existence, Durant

passed on to the most radical circles in the "bedlam" of

Manhattan. He tried -- and failed -- to convert Emma Goldman

and Alexander Berkman from anarchism to socialism. In 1911,

he became the teacher and (as he put it) chief pupil of the

Ferrer Modern School, an experiment in libertarian education.

A sponsor of the school, Alden Freeman, took a fancy to the

shy instructor and treated him to a summer tour of Europe to "broaden

his borders." Returning to the States, Durant fell in

love with one of his pupils, whose sprightly vivacity led him

to call her "Puck" and, in his writings, "Ariel" --

the names by which she became known to the rest of the world.

In order to marry her, in 1913 he

resigned his post as teacher and supported himself and her

by lecturing for five and ten-dollar fees, while Alden Freeman

paid his tuition in the graduate schools of Columbia University.

There, Durant took biology under Morgan and McGregor, psychology

under Woodworth and Poffenberger and philosophy under Woodbridge

and the legendary John Dewey.

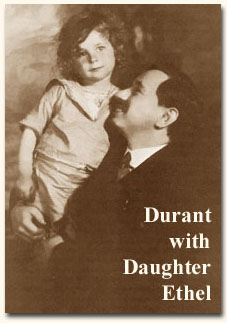

Shortly thereafter, the arrival

of his daughter, Ethel, slowly changed Durant's philosophy.

Faced with the daily miracle of living growth, he shed his

youthful atheism and returned to a more vital conception of

the world. In his "mental" -- but not literal --autobiography, Transition (1927),

he expressed the change with youthful sentiment:

Even before Ethel's coming I had

begun to rebel against that mechanical conception of mind

and history which is the illegitimate offspring of our industrial

age: I had suspected that the old agricultural view of the

world in terms of seed and growth did far more justice to

the complexity and irrepressible expansiveness of things.

But when Ethel came, I saw how some mysterious impulse, far

outreaching the categories of physics, lifted her up, inch-by-inch

and effort by effort, on the ladder of life. I felt more

keenly than before the need of a philosophy that would do

justice to the infinite vitality of nature. In the inexhaustible

activity of the atom, in the endless resourcefulness of plants,

in the teeming fertility of animals, in the hunger and movement

of infants, in the laughter and play of children, in the

love and devotion of youth, in the restless ambition of fathers

and the lifelong sacrifice of mothers, in the undiscourageable

researches of scientists and the sufferings of genius, in

the crucifixion of prophets and the martyrdom of saints --

in all things I saw the passion of life for growth and greatness,

the drama of everlasting creation. I came to think of myself,

not as a dance and chaos of molecules, but as a brief and

minute portion of that majestic process ... I became almost

reconciled to mortality, knowing that my spirit would survive

me enshrined in a fairer mold ... and that my little worth

would somehow be preserved in the heritage of men. In a measure

the Great Sadness was lifted from me, and, where I had seen

omnipresent death, I saw now everywhere the pageant and triumph

of life.

The birth of his daughter had the further effect

of ending the long separation between Durant and his mother.

Mother Durant came to see the infant -- what grandparent can

resist a grandchild? – and, in a glow of contentment,

she exclaimed, "It's a Durant!" The birth of his daughter had the further effect

of ending the long separation between Durant and his mother.

Mother Durant came to see the infant -- what grandparent can

resist a grandchild? – and, in a glow of contentment,

she exclaimed, "It's a Durant!"

In those years of plain living and

eager study, he paid little attention to history, which seemed

so discouraging a record of slaughter and politics. But Brisbane

had led him to read Buckle's Introduction to the History

of Civilization, as a guide to a more philosophical understanding

of man's past. Durant was deeply moved when he learned that

Buckle had died in Damascus, after writing merely the introduction

to what had been planned as a history of civilization, from

its origins to the 19th century. Durant resolved

to undertake the same task -- but he was 41 before he was free

to begin. Meanwhile, almost every day, he began to gather material.

In 1917, as a requirement for the

doctorate in philosophy, Will Durant wrote his first book, Philosophy

and the Social Problem, which argued that philosophy was

languishing because it avoided the actual problems of society.

The exuberant young author proposed to view these problems

from the perspective of philosophy and suggested that specific

training in administration should be made a qualification for

public office. He received his degree in 1917 and began to

teach the "dear delight" as an instructor in Columbia

University. But World War I disrupted his classes, and he was

politely dismissed from his post.

Meanwhile, in a former Presbyterian

Church now called Labor Temple, at 14th Street and

2nd Avenue, New York, he had begun those lectures

on the history of philosophy, literature, science, music, and

art which prepared him to write The Story of Philosophy and The

Story of Civilization. For his audiences there were mostly

men and women who demanded both clarity of exposition and some

contemporary significance in all historical studies. In 1921

he organized Labor Temple School, which devoted itself to adult

education.

One Sunday afternoon of that year,

E. Haldeman-Julius, publisher of the famous Little Blue Books,

happened to pass Labor Temple and noted from the announcement

board that at 5 p.m. Durant would talk on Plato. The publisher

entered, liked the lecture and later, from Girard, Kansas,

wrote and asked Durant to turn that lecture into one of his

little five-cent Blue Book publications. Durant initially refused,

on the ground that his other work was taking up all his time.

Here, at the outset, his literary career might have come to

an end. But Julius wrote again and enclosed advance payment.

Durant yielded and then again absorbed himself in teaching,

but Julius asked for a booklet on Aristotle -- again sending

payment in advance. This, too, was written, and again Durant

thought the relationship was ended. But the enterprising publisher

persisted until 11 booklets were delivered to him. History

would prove that these enterprises, undertaken very much against

his will, would create what would ultimately become a best

seller, for the 11 booklets became The Story of Philosophy.

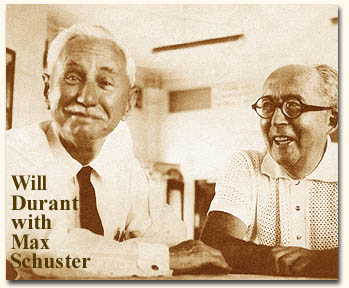

The amazing success of this book is an old

story in publishing circles. Dick Simon and Max Schuster, of

the new publishing firm Simon and Schuster, took over the booklets

and made them into a handsome volume. Durant expected a sale

of some 1,100 copies, and the optimistic publishers predicted

1,500. It was assumed that the subject and price – five

dollars in 1926 -- would frighten readers away. But a favorable

review by Henry Forman in the New York Times sent the

book off to a good start. In a few years it sold 2,000,000

copies. To this day it is still capturing new readers in America

and has found many abroad, in its translations into Chinese,

Czech, Danish, Dutch, Finnish, German, French, Hebrew, Hungarian,

Italian, Japanese, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Serbo-Croatian,

Spanish and Swedish. The amazing success of this book is an old

story in publishing circles. Dick Simon and Max Schuster, of

the new publishing firm Simon and Schuster, took over the booklets

and made them into a handsome volume. Durant expected a sale

of some 1,100 copies, and the optimistic publishers predicted

1,500. It was assumed that the subject and price – five

dollars in 1926 -- would frighten readers away. But a favorable

review by Henry Forman in the New York Times sent the

book off to a good start. In a few years it sold 2,000,000

copies. To this day it is still capturing new readers in America

and has found many abroad, in its translations into Chinese,

Czech, Danish, Dutch, Finnish, German, French, Hebrew, Hungarian,

Italian, Japanese, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Serbo-Croatian,

Spanish and Swedish.

It was this windfall that enabled

Durant to realize at last the ambition that had stirred within

him when he read of Buckle's abortive dream. He retired from

teaching and began work on his own history of civilization,

though, for a time, he allowed himself to be distracted by

writing magazine articles for tempting fees. Many of these

essays were collected into The Mansions of Philosophy (1929),

later to be reprinted as The Pleasures of Philosophy. But

in 1929 he turned his back on Mammon and resolved that he would

devote the remainder of his life to The Story of Civilization. He

used the word "story" to suggest his belief that

the narrative would be intelligible to any high school graduate,

but the word has misled many into thinking of this monumental

production as popularization. Those who wade into the volumes

are surprised to find them marked by painstaking scholarship,

by profuse detail, and by the philosophical perspective that

recalls Spengler's wish that only philosophers would write

history.

Originally, Durant planned to divide

the work into five volumes, to appear at five-year intervals.

For the first volume, Our Oriental Heritage (1935),

he circled the globe twice and wrote and rewrote its 1,049

pages in longhand, through six years, giving the history of

Asiatic civilization from the beginnings to Gandhi and Chiang

Kai-shek. In the preface he explained his purpose and method:

I have tried in this book to accomplish

the first part of a pleasant assignment which I rashly laid

upon myself some 20 years ago, to write a history of civilization.

I wish to tell as much as I can, in as little space as I

can, of the contributions that genius and labor have made

to the cultural heritage of mankind - to chronicle and contemplate,

in their causes, character and effects, the advances of invention,

the varieties of economic organization, the experiments in

government, the aspirations of religion, the mutations of

morals and manners, the masterpieces of literature, the development

of science, the wisdom of philosophy and the achievements

of art. I do not need to be told how absurd this enterprise

is, or how immodest is its very conception, for many years

of effort have brought it to but a fifth of its completion

and have made it clear that no one mind, and no single lifetime,

can adequately compass this task. Nevertheless I have dreamed

that, despite the many errors inevitable in this undertaking,

it may be of some use to those upon whom the passion for

philosophy has laid the compulsion to try and see things

whole, to pursue perspective, unity and understanding through

history in time, as well as to seek them through science

in space.

I have long felt

that our usual method of writing history in separate longitudinal

sections

-- economic history, political history, religious history,

the history of philosophy, the history of literature, the

history of science, the history of music, the history of

art -- does injustice to the unity of human life; that

history should be written collaterally as well as lineally,

synthetically

as well as analytically; and that the ideal historiography

would seek to portray in each period the total complex

of a nation's culture, institutions, adventures and ways. But

the accumulation of knowledge has divided history, like

science,

into a thousand isolated specialties, and prudent scholars

have refrained from attempting any view of the whole --

whether of the material or of the living past of our race.

For the

probability of error increases with the scope of the undertaking,

and any man who sells his soul to synthesis will be a tragic

target for a myriad merry darts of specialist critique. "Consider," said

Ptah-hotep 5,000 years ago, "how thou mayest be opposed

by an expert in council. It is foolish to speak on every

kind of work." A history of civilization shares the

presumptuousness of every philosophical enterprise: It

offers the ridiculous spectacle of a fragment expounding

the whole.

Like philosophy, such a venture has no rational excuse

and is at best but a brave stupidity, but let us hope that,

like

philosophy, it will always lure some rash spirits into

its fatal depths.

That same preface contained some

prophetic lines, written in 1934:

At this historic moment -- when

the ascendancy of Europe is so rapidly coming to an end,

when Asia is swelling with resurrected life, and the theme

of the 20th century seems destined to be an all-embracing

conflict between the East and the West -- the provincialism

of our traditional histories, which began with Greece and

summed up Asia in a line, has become no merely academic error,

but a possibly fatal failure of perspective and intelligence.

The future faces into the Pacific, and understanding must

follow it there.

Volume II, The Life of Greece (1939),

applied the "integral method" to Hellenic culture

from its oldest antecedents in Crete and Asia to its envelopment

by Rome. In the preface he proposed an all-embracing plan:

I wish to see and feel this complex

culture not only in the subtle and impersonal rhythm of its

rise and fall, but in the rich variety of its vital elements:

its ways of drawing a living from the land and of organizing

industry and trade; its experiments with monarchy, aristocracy,

democracy, dictatorship and revolution; its manners and morals;

its religious practices and beliefs; its education of children

and its regulation of the sexes and the family; its poems

and temples, markets and theaters and athletic fields; its

poetry and drama; its painting, sculpture, architecture and

music; its sciences and inventions; its superstitions and

philosophy. I wish to see and feel these elements, not in

their theoretical and scholastic isolation, but in their

living interplay as the simultaneous movement of one great

cultural organism, with a hundred organs and a hundred million

cells, but with one body and one soul.

Volume III, Caesar and Christ (1944),

told the story of Rome from Romulus to Constantine. In construction,

this volume is the best of Durant's books, moving as it does

with dramatic interest from Etruscan caves to Christian catacombs.

Maurice Maeterlinck sent from France an enthusiastic tribute:

This book is a magnificent

success, worthy of the greatest histories of mankind. It

is as complete

as an encyclopedia, but instead of being the moth-eaten labor

of an obscure compiler, it is the product of a great writer

and a great artist, and each of the pages is a page from

an anthology. The work has a continuous flow. It is luminous

and without blemish. It has none of the defects of the "best

sellers" composed of endless twaddle, paddings and platitudes.

Dr. Durant's pen seems to clarify, to light up, to simplify

everything it touches. At times one would believe he was

listening to Montesquieu.

Volume IV, The Age of Faith (1950),

was another Leviathan, running to 1,196 pages, but it covered

three civilizations -- Christian, Moslem and Judaic -- through

a thousand years, from Constantine to Dante, A. D. 325 to 1321.

It included some 200 pages on Mohammedan culture in its great

days at Baghdad, Cairo and Cordova. Never before has a Christian

scholar, in one volume on the Middle Ages, given such ample

recognition to the achievements of Islam in government, literature,

medicine, science and philosophy. And the three chapters on

medieval Jewish life show a surprisingly sympathetic understanding

of what might have seemed an alien culture. Professor Allan

Nevins, of Columbia University, wrote of this book:

I was specially pleased to have

Will Durant's The Age of Faith, which seems to me a very

remarkable feat of synthesis and interpretation. I regard

it as the best general account of medieval civilization in

print. Mr. Durant's great series of books should in time

become recognized -- if it is not already -- as one of the

outstanding works in American historiography.

Volume V, The Renaissance (1953), exemplifies

Durant's integral method by covering every phase of that exuberant

epoch in Italy. It began with Petrarch and Boccaccio in the

14th century, went on to Florence with the Medici

and the artists and humanists and poets who made Florence a

very Athens; told the tragic tale of Savonarola; passed on

to Milan with Leonardo da Vinci; to Umbria with Piero delta

Francesca and Perugino; to Mantua with Mantegna and Isabella

d'Este; to Ferrara with Ariosto; to Venice with Giorgione,

the Bellini and Aldus Manutius; to Parina with Correggio; to

Urbino with Castiglione; to Naples with Alfonso the Magnanimous;

to Rome with the great Renaissance popes and their patronage

of Raphael and Michelangelo; to Venice again with Titian, Aretino,

Tintoretto and Veronese; and back to Florence with Cellini. Volume V, The Renaissance (1953), exemplifies

Durant's integral method by covering every phase of that exuberant

epoch in Italy. It began with Petrarch and Boccaccio in the

14th century, went on to Florence with the Medici

and the artists and humanists and poets who made Florence a

very Athens; told the tragic tale of Savonarola; passed on

to Milan with Leonardo da Vinci; to Umbria with Piero delta

Francesca and Perugino; to Mantua with Mantegna and Isabella

d'Este; to Ferrara with Ariosto; to Venice with Giorgione,

the Bellini and Aldus Manutius; to Parina with Correggio; to

Urbino with Castiglione; to Naples with Alfonso the Magnanimous;

to Rome with the great Renaissance popes and their patronage

of Raphael and Michelangelo; to Venice again with Titian, Aretino,

Tintoretto and Veronese; and back to Florence with Cellini.

The preface to Volume VI, The

Reformation, describes the book and reveals the man:

We begin by considering religion

in general, its functions in the soul and the group and the

conditions and problems of the Roman Catholic Church in the

two centuries before Luther. We shall watch England and Wyclif

in 1376-82, Germany and Louis of Bavaria in 1320-47, Bohemia

and Huss in 1402-85, rehearsing the ideas and conflicts of

the Lutheran Reformation. And, as we proceed, we shall note

how social revolution, with communistic aspirations, marched

hand-in-hand with religious revolt. We shall weakly echo

Gibbon's chapter on the fall of Constantinople and, shall

perceive how the advance of the Turks to the gates of Vienna

made it possible for one man to defy at once an emperor and

a pope. We shall consider sympathetically the efforts of

Erasmus for the peaceful self-return of the Church. We shall

study Germany on the eve of Luther and may thereby come to

understand how inevitable he was when he came.

In Book II, the Reformation proper

will hold the stage, with Luther and Melanchthon in Germany,

Zwingli and Calvin in Switzerland, Henry VIII in England,

Knox in Scotland and Gustavus Vasa in Sweden, with a side

glance at the long duel between Francis I and Charles V.

And other aspects of European life in that turbulent half-century

(1517-64) will be postponed in order to let the religious

drama unfold itself without confusing delays.

Book III, will

look at "the

strangers in the gate": Russia and the Ivans and the

Orthodox Church; Islam and its changing creed, culture and

power; and the struggle of the Jews to find Christians in

Christendom. Book IV will go "behind the scenes" to

study the law and economy, morals and manners, art and

music, literature and science and philosophy of Europe

in the age

of Luther. In Book V we shall be forced to admire the calm

audacity with which she weathered the encompassing storm.

In a brief Epilogue we shall try to see the Renaissance

and the Reformation, Catholicism and the Enlightenment,

in the

large perspective of modern history and thought.

Can so controversial a subject be

treated impartially? Durant professes to have tried but, as

yet, his success is difficult to assess. His preface concludes

disarmingly:

It is a fascinating but difficult

subject, for almost every word that one may write about it

can be disputed or give offense. I have tried to be impartial,

though I know that a man's past always colors his views,

and that nothing else is so irritating as impartiality. The

reader should be warned that I was brought up a fervent Catholic,

and that I retain grateful memories of the devoted secular

priests, and learned Jesuits, and kindly nuns, who bore so

patiently with my brash youth. But he should note, too, that

I derived much of my education from lecturing for 13 years

in a Presbyterian Church under the tolerant auspices of sterling

Protestants like Jonathan C. Day, William Adams Brown, Henry

Sloane Coffin and Edmund Chaffee, and that many of my most

faithful auditors in that Presbyterian Church were Jews,

whose search for education and understanding gave me a new

insight into their people. Less than any other man have I

excuse for prejudice, and I feel for all faiths the warm

sympathy of one who has come to learn that even the trust

in reason is a precarious faith, and that we are all fragments

of darkness groping for the sun. I know no more about the

ultimates than the simplest urchin in the streets.

What was he like, this patient Sisyphus

of history, who every five years rolled a heavy volume up the

high hills of scholarship and to the pinnacle of print, only

to begin at the bottom again? A labor he would indulge in until

no less than eleven volumes of The Story of Civilization were

completed. We know that he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for

the tenth volume in the series (along with his wife, Ariel,

who became his collaborator on the series after Volume VII:

The Age of Reason).

Photographs reveal Durant to be

a man of sparkling eyes and abundant hair, dressed immaculately.

Even those who were not friends spoke well of him. Durant embodied

the two qualities that he once declared no philosophy or philosopher

was complete without: understanding and forgiveness.

He never once attempted to build

his reputation at the expense of others; instead he sought

to better understand the viewpoints of human beings, and to

forgive them their foibles and human waywardness. When two

burglars were apprehended by police after having broke into

his Los Angeles home and stealing valuable jewelry and savings

bonds – Durant refused to press charges and insisted that

they be set free. "Forgiveness," again, is the other

half of philosophy.

Durant’s love for his wife Ariel only

deepened with the passing of time. When he was admitted to

hospital with heart problems in 1981 at the age of 96, his

wife stopped eating; perhaps fearing that he would not be returning.

When Durant learned of the death of his beloved wife, his own

heart stopped beating. They are buried beside each other in

a small Los Angeles cemetery, together for all eternity. Durant’s love for his wife Ariel only

deepened with the passing of time. When he was admitted to

hospital with heart problems in 1981 at the age of 96, his

wife stopped eating; perhaps fearing that he would not be returning.

When Durant learned of the death of his beloved wife, his own

heart stopped beating. They are buried beside each other in

a small Los Angeles cemetery, together for all eternity.

Unlike the cloistered academics

who turned up their noses at Durant’s attempt to bring

philosophy back to the common man, Durant was not content merely

to write about such subjects, he actually did his best to put

his ideas into effect. He had fought for equal wages, women’s

suffrage and fairer working conditions for the American labor

force. Durant had even drafted a "Declaration of Interdependence" in

the early 1940s – preceding the "Civil Rights Movement" by

some two decades – calling for, among many things:

Human dignity and decency,

and to safeguard these without distinction of race or color

or

creed; to strive in concert with others to discourage animosities

arising from these differences, and to unite all groups in

the fair play of civilized life…Rooted in freedom, children

of the same Divine Father, sharing everywhere a common human

blood, we declare again that all men are brothers, and that

mutual tolerance is the price of liberty.

He pursued this issue of racial

equality so vigorously that this Declaration was introduced

into the Congressional Record on October 1, 1945.

Over the years, Durant’s reputation

as a philosopher and historian has grown; his writings, which

have sold over 17 million copies, have been enjoyed by individuals

from all walks of life. Among his most impassioned readers

(and friends) were Mahatma Gandhi, George Bernard Shaw, Clarence

Darrow and Bertrand Russell – although it was always for

the common man, rather than the scholastic or academic audience,

that Durant wrote.

"We could do almost anything

if time would slow up," he once said, adding "but

it runs on, and we melt away trying to keep up with it." And

yet even time never covered 110 centuries in fifty years.

By the editors of Wisdom magazine

and John Little

.

|